By Abraham Uwuasom

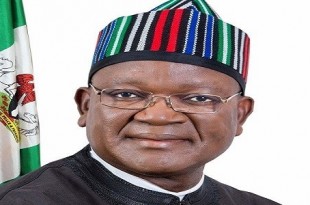

The call by Dr. Samuel Ortom, the governor of Benue State, for the nationwide adoption of the ranching of cattle could not have come at a better time.

The governor was speaking in the wake of the first month of his state’s Open Grazing Prohibition and Establishment of Ranches law, signed into force on November 1st.

The law restricts the grazing of animals to ranches, limits their movement to rail and truck, and punishes cattle rustling and attacks on farmers, among others. The state’s Livestock Guards has also been inaugurated to help enforce the law.

With the arguable exception of Ekiti State’s Governor Ayo Fayose, Ortom has been the nation’s most consistent voice on the viable resolution of the deadly confrontations between herdsmen and sedentary communities that have erupted across the country with increasing frequency.

This is unsurprising, because Benue State has been at the epicentre of these disturbances. Renowned for its agricultural prowess, the state has been a major grazing destination for nomadic herdsmen whose clashes with farmers in host communities have resulted in significant losses of life and destruction of property.

Between 2013 and 2016, an estimated 1,878 lives were lost in these clashes, with 750 wounded and 200 missing. An estimated N95 billion was lost between 2012 and 2016. Schools, hospitals, bridges and other social infrastructure have been destroyed, and the resultant unrest has negatively impacted commercial and social life throughout the state.

By making the ranching of cattle and other animals mandatory, the law is simply insisting on the modernisation of an activity which has stagnated in the medieval era for too long.

In agricultural superpowers like Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile and the United States, ranching has been standard practice for decades. The practice enables animals to be grazed within the confines of ranches which can be hundreds of thousands of acres in size, thereby facilitating their care and processing for agro-allied industry.

Instead of being exposed to the elements, vulnerable to cattle rustlers and other hazards, the animals raised on ranches are better protected, are less likely to encroach on farmland, and help put agriculturally unproductive land to better use. Cattle raised on ranches are almost always far more robust and healthier than their open-grazed counterparts.

Herdsmen are freed from the rigours of nomadic life, as they are no longer forced to wander across the nation in search of pasture and water for their animals. Their families can enjoy healthcare, education and other benefits of sedentary life without sacrificing their attachment to the cattle they value so highly.

The Benue anti open-grazing law has sought to be scrupulously fair by containing safeguards for all parties. Section 19 protects livestock from theft, while Section 20 protects farmers from attacks.

Ekiti State was the first to promulgate laws against open-grazing, but Benue State appears to have shown the way forward on the vexed issue of herdsmen-settler clashes. Its combination of consistent advocacy and carefully-worded legislation could succeed where threats and coercion have failed.

Much remains to be done, however. The practical concerns raised by stakeholders like the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN) must be addressed. MACBAN has claimed that the process of acquiring land for ranches is difficult and that no provision has been made for legal cattle markets in the state. If these fears are speedily addressed, they might help to reverse the alleged exodus of herdsmen out of the state since November.

Other states should follow the Benue example. Legislation should not target herdsmen as an ethnic group, nor seek vengeance for the past, but should ensure that cattle-grazing is simultaneously modernised, safe and turned into an economic benefit instead of a security threat.