This report is sponsored by Alliance for Action on Pesticides in Nigeria (AAPN), as part of its national campaign to raise awareness about the dangers of Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) and to promote safer, sustainable alternatives for Nigerian farmers.

By Abdulrahman Aliagan

July 2025 | Kwara State, Nigeria

Edu LGA, Kwara State — In the golden light of early morning, the rice fields of Lafiagi stretch out like a shimmering sea. It’s a scene of beauty, but one that hides a deadly secret.

For 29-year-old Abubakar Sodiq, it was his final view. After spraying his farm with a cheap, unlabelled pesticide purchased from the local market, Sodiq collapsed in the dirt, gasping for air. Within hours, he was dead. “I still remember the foam at his mouth,” his grieving sister told this reporter, clutching a faded photo. “He just wanted to grow rice. He didn’t know he was inhaling poison.”

Sodiq is one of many in Kwara State—and across Nigeria—who have become victims of Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs): a class of agrochemicals so toxic that many have been banned in Europe, the U.S., and parts of Asia, yet remain freely sold in Nigerian markets with little oversight.

In a country where agriculture employs more than 60% of the rural workforce, pesticides have long been seen as a shortcut to success. With immediate and visible results, their appeal is undeniable. But behind the promise of higher yields lie staggering human and environmental costs.

A 2024 field survey by a local health NGO in Kwara state found that over 70% of farmers reported nausea, dizziness, skin burns, or respiratory distress after using herbicides such as paraquat, glyphosate, and chlorpyrifos. These chemicals are often sold in unlabelled or foreign-labeled bottles, making it difficult for farmers to understand proper application or safety protocols.

In Asa LGA, Mama Bola, a respected elder in a women’s farming collective, lifts her sleeve to show darkened scars on her arm. “We use it because it works fast,” she explains. “But every time I spray, my body itches. One of our women lost her pregnancy after using it.”

In most cases, these farmers have no access to gloves or masks. Many don’t even know they’re supposed to use protective equipment. Instead, they carry out their work barefoot, unprotected, and unaware of the slow poison seeping into their lives.

On the commercial side, pesticide vendors face little regulation. At Oja Oba Market in Ilorin, traders openly sell banned chemicals—some directly from wheelbarrows. “We sell what farmers want,” said one trader. “Nobody checks us. No one from government has ever asked me what I sell.” Bottles on the shelves lack expiry dates. Others are labeled in Chinese. Some are expired but still used.

The health crisis does not end at the farm. In towns and cities across Kwara—Ilorin, Offa, Patigi, and beyond—consumers are increasingly exposed to pesticide-contaminated food.

Sherifat Ibrahim, a rice farmer and mother of three, recalls one frightening experience: “I bought okra from the market. After cooking, it turned black. I didn’t serve it. I threw everything away.” After several similar incidents, she began transitioning to organic methods, including composting and using fermented organic sprays.

Along the Asa River, fishermen complain of dying fish, while families who use the water for bathing and cooking report increased rashes and stomach issues. A nurse at Jalala Primary Health Centre in Ilorin South who refused her name to be mentioned explains:

“We mostly record cases as malaria. But deep down, we suspect chemical poisoning. We have no tools to diagnose it, and no training.”

A 2022 study by Ekundayo D.E, Sawyerr H.O, Opasola O.A, and Atimiwoaye A.D from the Department of Environmental Health Science, Kwara State University, conducted a cross-sectional study on the health effects of pesticide exposure among 310 farmers in Kwara North. Their findings were alarming: 81.6% of farmers used pesticides regularly and 42.1% experienced at least one form of health complication. These included neurological, reproductive, respiratory, and metabolic disorders.

The study also found a statistically significant link between pesticide exposure and health damage, with a P-value of 0.000, indicating urgent public health concern. “It’s not just misuse—it’s lack of access to education and protective gear,” said Dr. Ekundayo. “Most farmers don’t read labels, or the labels aren’t even readable.”

Not all farmers share the same alarm. In Molete, a village in Moro LGA, Aminullahi Abdullahi, a seasoned farmer, offered a contrasting perspective. “It depends on application,” he insisted. “Agrochemicals and organic substances both work. But you must know how and when to apply them.”

Farmers Abdullahi Aminullahi and Zurajudeen Adam in Molete Moro Local Government Area of Kwara State

He explained that certain chemicals are meant for weeding, others for post-weeding, and some for post-seedling application. “If you misuse them, you damage your crops or your health. But if used rightly, they are effective and safe.”

Aminullahi emphasized that most chemicals come with instructions. “We are told to wear gloves and cover our nose. The precautions are there. It’s up to us.”

Aminullahi also cautioned against mixing both organic and synthetic methods. “You can’t combine them. It will kill the farm,” he said flatly. “They must be applied separately.” Interestingly, he pointed out that dove droppings are richer in nutrients than cow dung and often yield better organic results.

Still, he admitted: “Agrochemicals give more harvest. But we are told that organics are safer—even if smaller in quantity. I have never seen anyone get sick from agrochemicals. But I know not everyone uses them properly.”

To him, the issue is technical and knowledge-based. Certain chemicals work for maize but not cassava, and vice versa. “If you know your crop and your chemical, you can manage it. It’s when people apply blindly that they suffer.”

In Irepodun LGA, Jumoke Adebayo and her cooperative are thriving using natural methods—compost, neem sprays, and intercropping.

“We’ve built trust with our customers. People call ahead to book,” Jumoke said. She also reported better health outcomes: no rashes, no coughing fits after spraying, and healthier soil. In Baruten, Fulani women like Hauwa Bala make biopesticides from neem leaves, chili, and garlic. “It works and it’s safe,” she said. “And it costs almost nothing.”

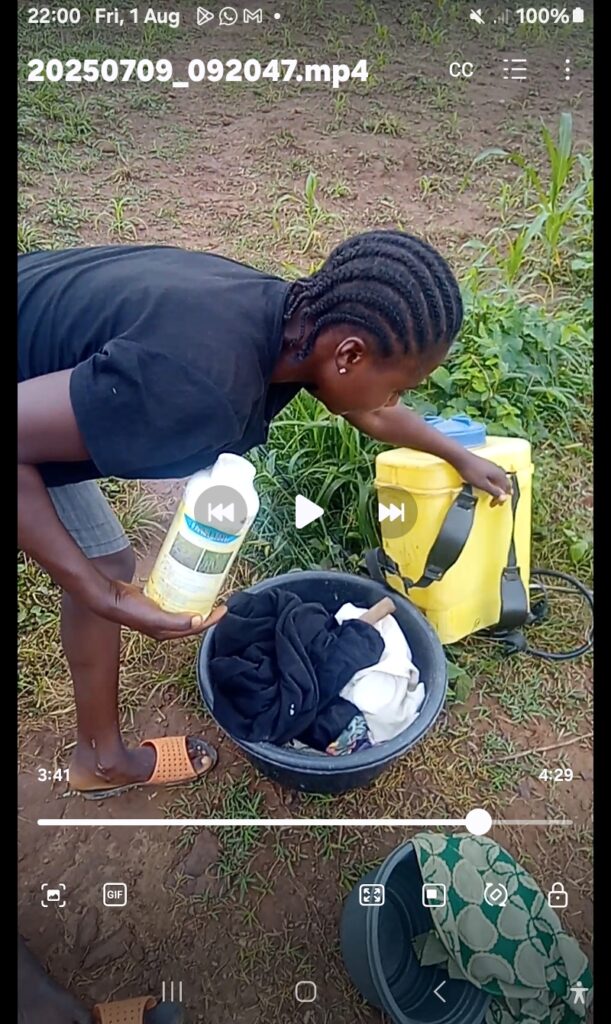

Adding to this narrative, Blessing Levinous, a farmer from Baruten Local Government Area, shared her firsthand experience with agrochemicals. “My name is Blessing Levinous, I am from Baruten Local Government Area of Kwara State. I am a farmer and I do use agrochemicals.

“In fact, you are meeting me on my farm and I want to go and spray chemicals. This chemical that I want to go and spray is to kill the grass so that the rice can grow very well. The chemical has not been causing problems, because I was trained on how to apply it. But I used to hear that it used to affect some people at times.

“There is a way that one can apply it. If one applies it and doesn’t cover his nose, it may affect somebody. Somebody like me—I cover my nose when I am applying it.”

She further explained, “If we apply the chemical, it usually to makes the harvest more plentiful.

“As to your question on wether I know anybody who the chemical has affect. “I don’t know anybody the chemicals have caused any damage when it comes to health issues, like I said earlier, I used to hear it. I used to hear that it used to affect people if it is not properly applied. Some said it can cause skin rashes, some said it can cause unhealthy breathing.

“But we have learned how to use it and we have been trained on how to use it. The name of the chemical that we are using, we used to call it ‘Select’. And if I apply two cups with water that will fill my containers and from there we spray. But what I know is if it is too much or we apply more than prescribed, it can kill the grass and the crops. So, you have to apply it in the right way. We use it in rice and even cassava cultivation.”

All voices — whether organic advocates or chemical defenders — agree on one thing: farmers need more knowledge. Farm extension services have collapsed. Government inspectors are largely absent. Most farmers are self-taught or rely on word-of-mouth advice.

“Nobody trained me,” said Abdulrasheed Abibat. “We just learn from mistakes.” This systemic neglect has allowed harmful practices to flourish.

Beyond human health, the environment is suffering. Soil quality is degrading. Rivers are polluted. Natural predators like bees and frogs are disappearing. In some parts of Kwara, land has become infertile due to overreliance on chemicals—forcing farmers to clear more forested land to stay productive.

From farmers to health workers, to researchers, the consensus is growing: Nigeria needs a new approach. Experts recommend the immediate ban on internationally outlawed pesticides, mandatory labeling in local languages, widespread farmer training.

They also want agroecological education, equipping primary health centers to treat pesticide-related ailments, support for organic fertilizer production at the community level, and revival of extension services to offer regular field advice.

The media must tell these stories—of both death and hope. Civil society must pressure policymakers. Researchers must make data accessible to the public. “We need to move from poison to productivity,” said an agricultural officer in Kaiama, requesting anonymity. “But we can’t do that with silence.”

Kwara’s farmers stand at a critical crossroads. One path is faster but deadly. The other is slower but sustainable. This is no longer a technical issue alone. It is about justice, dignity, and survival. It is about making sure the hands that feed us do not pay the ultimate price.

“Let us farm for life,” said Jumoke, standing proudly over her thriving organic plot, “not for death.”

This feature is part of a nationwide documentation effort to expose harmful pesticide use, amplify farmer voices, and promote the adoption of safer, sustainable farming practices across Nigeria.

Abdulrahman Aliagan, Kwara Field Correspondent | Time Nigeria Magazine

- This report is being sponsored by Alliance for Action on Pesticides in Nigeria (AAPN).