By Aliyu Gerengi, Gombe

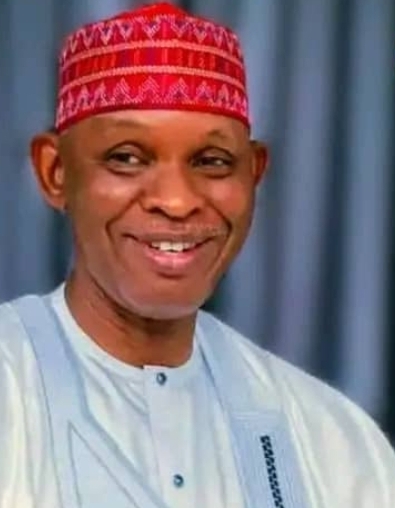

The defection of Kano State Governor, Abba Kabir Yusuf, from the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP) to the All Progressives Congress (APC) has sent shockwaves across the state’s political landscape, drawing mixed reactions, reopening old wounds, and reshaping calculations ahead of the 2027 general elections.

While the move has been welcomed by some political heavyweights as a strategic realignment, others have described it as yet another episode in Kano’s long history of political betrayals, alliances of convenience, and shifting loyalties.

Defending the governor’s decision, prominent political figures including Professor Rufa’i Ahmed Alkali, former National Chairman of the NNPP; Senator Sulaiman Othman Hunkuyi, former National Organising Secretary of the party; and Professor Bem Angwe, former National Legal Adviser, argued that Yusuf’s exit was neither impulsive nor treacherous.

According to them, the defection was a calculated response to deep-rooted internal crises that have plagued the NNPP since the 2023 elections—ranging from factional disputes and leadership tussles to weak institutional structures at the state and national levels.

They maintained that governing Kano, a politically sensitive and populous state, requires stability and freedom from endless party infighting. In their view, Yusuf’s move to the APC offers him a broader platform, stronger federal alignment, and political breathing space to focus on governance.

However, the defection has also reignited a broader conversation about politics, loyalty, and betrayal within the famed Kwankwasiyya movement led by former Kano State Governor and NNPP presidential candidate, Senator Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso.

Critics argue that Kwankwaso, once celebrated as a political godfather who built a mass movement of loyalists, has over the years lost several key allies who rose to prominence under his political structure—only to later part ways under bitter circumstances. They point to the defection of Abdullahi Ganduje to the APC, the eventual fallout with Abba Yusuf, and the exit of other former protégés as evidence of a recurring pattern of strained relationships and political divorce.

To these critics, Yusuf’s defection is not an isolated incident but part of a longer trajectory in which Kwankwasiyya allies, once firmly united, eventually drift away—often accusing the movement of excessive central control, intolerance of dissent, and personality-driven politics.

Supporters of Kwankwaso, however, reject this narrative, insisting that defections are driven more by personal ambition than ideological differences. They argue that political loyalty must be grounded in principles, not convenience, and that history will judge those who abandon platforms that brought them to power.

As reactions continue to pour in, analysts agree on one point: Abba Yusuf’s defection has significantly altered Kano’s political equation. With the governor now aligned with the APC, the ruling party stands to consolidate power in the state, potentially weakening the NNPP ahead of 2027. The move could also trigger further defections, redraw alliances, and intensify competition between APC and NNPP loyalists across Kano’s political structures.

For Kano voters, the coming months will test whether the defection translates into improved governance, stronger federal support, and political stability—or whether it deepens cynicism about elite politics, where party platforms are often secondary to personal survival.

As Nigeria’s political history has repeatedly shown, defections are rarely the end of a story. In Kano, Abba Yusuf’s move to the APC may well be the opening chapter of a new, more intense struggle for power as 2027 draws closer.